Hello! 👋

This is a demo of how the 🏝️ Islands architecture principle is implemented within 🚀 Astro, and accompanies my "Astro Islands: Beyond Framework Borders" talk.

This demo aims to explain the logic behind the principle, why it exists, and how it is implemented within the web framework Astro to provide better performance.

This page contains a few components that are rendered as islands, and styled as such to stand out.

About Islands

Let's quote Astro directly first:

An “island” refers to any interactive UI component on the page. Think of an island as an interactive widget floating in a sea of otherwise static, lightweight, server-rendered HTML.

The islands architecture is a principle of only shipping JavaScript for specific parts of a webpage or website, rather than the whole page. When a website only contains a few components that require any interactivity, it makes less sense for the static parts, like text and images, to also be rendered with JavaScript.

Let's look at an example of a website that would benefit from the islands architecture. Fathom Analytics is a privacy-conscious analytics provider that I've enjoyed using, and have a landing page with fairly minimal JavaScript, so I'll use that. Here's their landing page (as of February 2024):

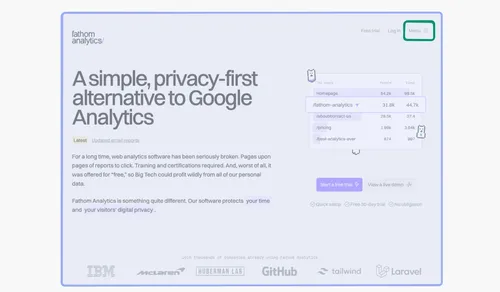

This page has a single bit of interactivity above the fold (i.e. the bottom of the browser window), which is the Menu button in the top-right corner. Clicking the Menu button opens a side menu containing further links. Let's visualise this as a sea of content highlighted in blue, with the interactive part highlighted in green:

As you can see, JavaScript is used for a minimal part of this webpage. The rest is content that can be rendered on the server, and sent as HTML and CSS only. There is no need for JavaScript to render that content.

Why are Islands a good thing?

Because the web has unfortunately begun to load excessive amounts of JavaScript, sometimes needlessly, and sometimes as a result of popular web frameworks like React.

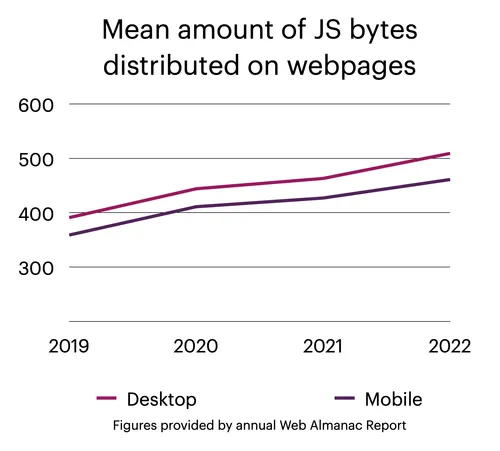

The Web Almanac is an annual report carried out by HTTP Archive, an open-source initiative to analyze the current state of the public Internet by crawling websites and recording detailed information. Their last 4 reports (2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022) were released, and shows details of JavaScript usage across these websites, amongst a bunch of other statistics.

Year-on-year, the reports have found the mean amount of JavaScript shipped to browsers per webpage has increased, both on desktop and mobile.

Shipping JavaScript to the browsers is sometimes an enjoyable necessity, but overuse can result in:

- Increased page loading times for downloading and parsing

- Blocks rendering of other page content

- Higher device resource usage, such as the device's battery

When React arrived and gained a massive amount of popularity in the

mid-2010s, it turned websites into full JavaScript machines whether they

needed it or not. The HTML shipped to the browser typically contained a

single element (usually <div id="app"></div> ), and the entire website was rendered with JavaScript into that

element. It meant the burden of rendering a website was passed onto the

browser, rather than rendered on the server like websites built with

your favourite languages like PHP.

Since the hey-day of React and other JavaScript UI libraries and frameworks, other frameworks have popped up to bring different rendering strategies and improve rendering performance. The main one for React is arguably Next.js, which renders as much of the React codebase on the server as it can, and streams the resulting HTML to the browser, as well as JavaScript to "hydrate" the page (i.e. load and parse the JavaScript, and make any components that need it interactive).

While this approach did work to improve performance, it still came with a caveat. Next.js needs to hydrate the whole page, static content included, and not just the components that actually need interactivity. This means there is still a potentially-substantial amount of JavaScript being sent to the browser to parse. The islands architecture contrasts this by only shipping JavaScript for the components that actually need it.

Islands within Astro

I won't go too into detail as Astro already have a great write-up on how Islands work and how to use them, but I'll give some of the basic stuff here.

Astro is a "server-first" web framework. It's aimed specifically at content-rich websites, to make creating pages as easy and enjoyable as possible, whilst maintaining a high bar on performance.

One really awesome feature of Astro is the ability to use a mixture of UI frameworks at the same time, on the same website. This is great if you're migrating from an existing website, or want to try different frameworks within the same site, or you know one framework is rubbish to use with certain things (my mind straightaway goes to working with forms in React) and you'd rather use another.

I said Astro is a "server-first" web framework earlier, and by that, I mean Astro renders all content at build-time on a server, before a website is deployed. If you pass Astro a component written with React, for example, it will render that component's HTML, and the resulting output contains zero JavaScript. That is Astro's default behaviour, and maintains that JavaScript is a feature to opt in to using, rather than receiving by default whether it is needed or not.

When you do need a component to by rendered with JavaScript intact though, you can tell Astro through "client directives". These are attributes that tell Astro which components to hydrate in the browser, and when they should be hydrated.

Here's an example:

/*

* Say <Carousel /> is a React component.

* The following will tell Astro to render its HTML only

*/

<Carousel />

/*

* Adding a client directive like `client:idle`, tells Astro

* that this component needs to be hydrated with JavaScript in

* the browser. In this case, the JS will be loaded when the

* browser becomes "idle" (i.e. not doing any heavy work).

*/

<Carousel client:idle />

In the example above, the <Carousel /> component is given the client:idle attribute,

which tells Astro to hydrate the component with JavaScript when the browser

is idle.

There are more client directives too, which extends the power of Astro's

ability to hydrate components when needed. The full list is in their docs, and the best one is probably client:visible .

Demo time!

Enough waffling, how about some live examples?

First off, this webpage is created in Astro, and contains a mix of static Astro components, and UI libraries like React and Svelte just for fun. I've added the icons for which framework is powering each island too, so you can see there's a mix!

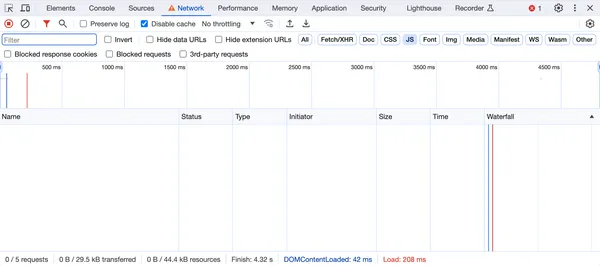

If you happen to be viewing this on a desktop browser, you could scroll up to the top of the page, open up the browser developer tools, go to the Network tab, and then hit refresh in the browser. Up until this demo section, you should see that zero JavaScript resources have been needed loaded. For the benefit of those viewing this on a mobile browser, it should look like this:

Now that you've scrolled down to this section though, there would have been some JavaScript popping up. That JavaScript is powering the island on the right, which will display logs as we interact with the islands below. However, because the logs are not viewable by those on a mobile device, the JavaScript will only be loaded for those on a desktop browser! The logs that are displayed within that island are being stored in a local JavaScript store, powered by a dependency called nanostores.

Time for our first second demo island. Earlier, I showed

an image of a graph, visualising the increase in the mean number of JavaScript

bytes sent to webpages over the last few years. Let's create an interactive

version of that graph!

I've chosen React for this component, and used react-chartjs-2 + Chart.js to make things fairly simpler.

Interactive graph

Mean amount of JS bytes distributed on webpages

Figures provided by annual Web Almanac Report

I loaded that by telling Astro that this is a client component, but

using the client:visible attribute to tell

Astro to load it when the component is visible. Here's the full code snippet:

/*

* <Island /> is my own component to add island styles,

* a title and a framework icon

*/

<Island title="Interactive graph" framework="react">

<Graph client:visible />

</Island>

So next, let's grab some data through an API call and display it. Below is a component I created for my own website that makes a request to an API of my own, and grabs 5 of my most-played songs recently from my own Spotify account. The component takes that response and renders the list of (potentially-embarrassing) tracks.

Joe's recent top tunes

From Spotify

Loading

Just like before, this island only loaded when we scrolled down to it. If we wanted to though, we could set up Astro to use Server-Side Rendering, and fetch and render this data at run-time on the server to be displayed. Just like the good ol' days.

Finally, something more fun. My friends at Medayo created an API for me that would make the same call for my top Spotify songs as above, but then ask ChatGPT to generate something interesting based on those songs. I've then added a selection of what type of content we'd like. Want a cringey song? No prob.

ChatGPT demo

Once again, this island is only rendered when the island is visible. The

main thing to note here though is that this API call can be pretty slow

to respond, as it's asking ChatGPT for a response, and so there is an

advantage to calling the API sooner rather than later. To do that, Astro

allows passing in a rootMargin to

the client:visible attribute, meaning

Astro will start to hydrate that island's JavaScript when the margin around

the island enters the browser viewport, saving a bit of time.

<Island title="ChatGPT demo" framework="vuejs">

<Chatty client:visible={{ rootMargin: "400px" }} />

</Island>

Wrap up

The islands architecture principle helps us web developers gain a little more control over the JavaScript we send to users. JavaScript is not a bad thing - it's essential for some of the best experiences on the web. There are also some projects where client-side rendering is still acceptable, such as JavaScript-rich dashboards or mapping applications. For most of the rest of the websites on the web though, JavaScript should be treated as a commodity.

Probably the best thing about the islands approach within Astro is the server-first approach. By making static content the default output of all components, it means the developer is explicitly opting in to sending JavaScript to the browser, rather than something that may be discovered down the line when a site is deployed. It makes the whole action of sending JavaScript more intentional.

Astro is not alone in this space too. Marko, a declarative UI framework created by eBay engineers, uses a similar approach of partial hydration to send only the minimal JavaScript needed. Fresh is a web framework that runs on Deno and also uses islands (and created this really helpful guide to islands too). All of these frameworks are pushing the limits of ensuring JavaScript is used and sent more responsibly than before.

Thanks for reading! The code for this demo is also available on GitHub, so do have a dig through the code if you're curious.